photo credits: Gina Clyne (OXY ARTS), Juliet Hinely and Austin Thomason (UMICH)

For Your Eyes Only

OXY ARTS, Los Angeles, CA: June 3 - July 29, 2023

Fine Arts Center Gallery, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville: January 20 - February 27, 2022

NADA House, Governor’s Island, New York City; May 4 - August 1, 2021

University of Michigan Institute for the Humanities, Ann Arbor: Feb 15 - April 16, 2021

Essay by Lia Nazemian for debut presentation of For Your Eyes Only, 2021:

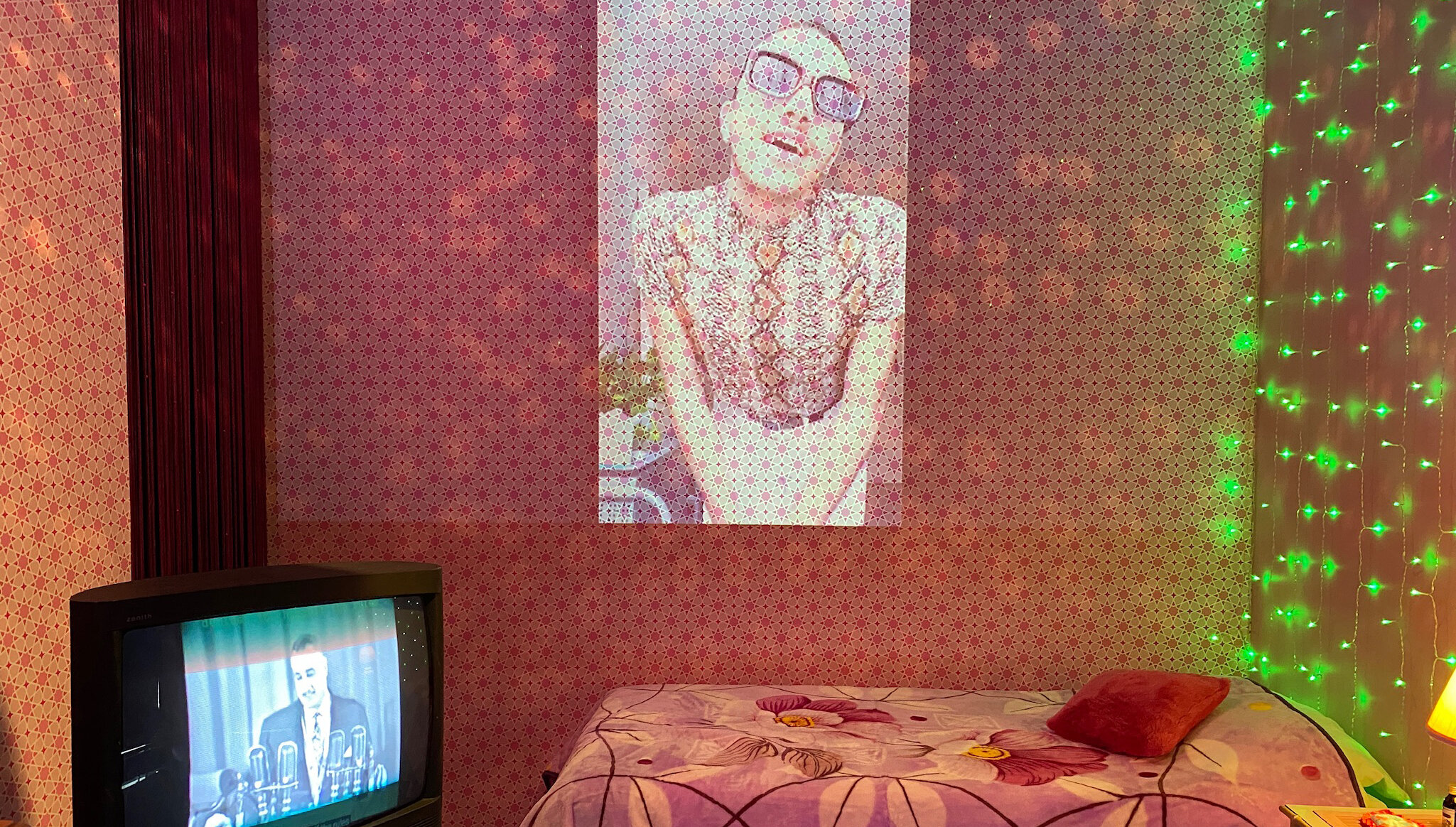

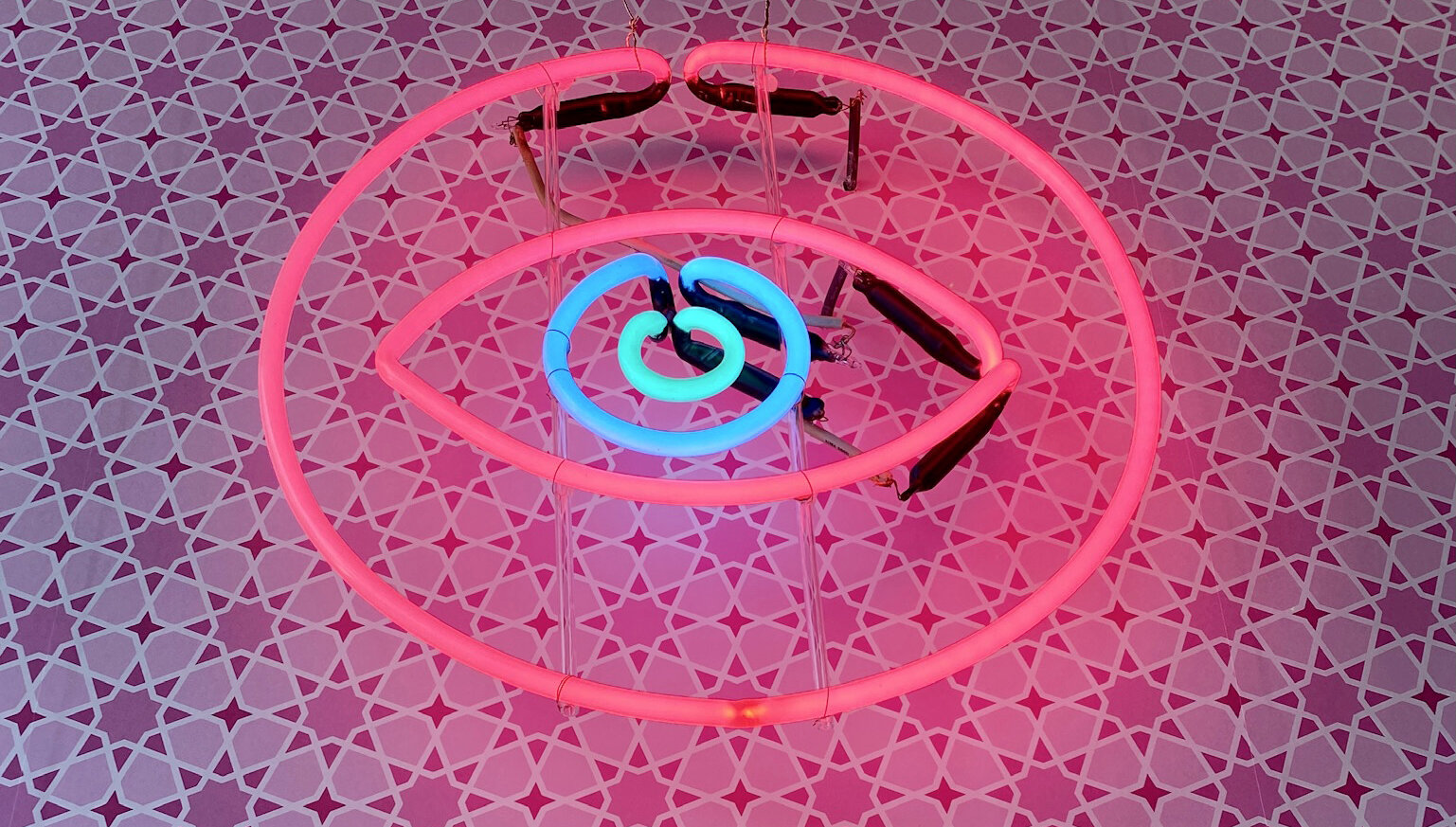

Yasmine Nasser Diaz’s For Your Eyes Only (FYEO) is an installation imbued with the experiences of many, yet wholly encapsulating the personal. A new iteration of her bedroom installation series at the University of Michigan’s Institute for the Humanities Gallery, FYEO is a publicly visible interior of a bedroom drenched in pink geometric patterned wallpaper. What will surely first attract the viewer’s eye is the large-scale projection of women and non-binary persons dancing in a reel of selfie videos. A second video which plays on a ‘90s-era television set, is a documentary-style montage of news clips featuring women-led political rallies from around the Global South woven alongside speeches by political figures from the 1950s up to the present. The two-channel video installation plays at the backdrop of a minimalist house track composed by the Beirut-based Carol Abi Ghanem, aka DJ El Shaar. A rose-colored disco ball shines upon the contents of the space: a bed, a vanity mirror set and a glaring pink neon light in the shape of an “evil eye.” On the floor lie objects one would expect to see at a protest protruding from a backpack: protective eye goggles, a megaphone, a small first aid kit, a water bottle, sanitizer and an ACLU pocket ‘know your rights’ booklet. The installation is both inherently private because of its contents, yet unavoidably voyeuristic due to its visibility from the exterior of the university campus. Nevertheless, the space Diaz has so assiduously assembled feels personal and safe while simultaneously giving off the illusion of being in an electrifying rave.

Third culture identity and the tensions around growing up in the U.S. as a female-identifying immigrant youth has been a subject Diaz has returned to in her practice. Previously the focus was on the climate of the ‘90s which also corresponded to the artist’s own experiences. While the TV set in this installation is still a clear nod to that era and legacy, the incorporation of Instagram stories and TikTok clips, as well as the placement of supplies and protective gear for protesting is a direct response to the technologies and social movements of this contemporary moment. Nasser Diaz created the dancing montage from actual clips that SouthWest Asian/North African (SWANA) individuals, primarily from the diaspora, posted of themselves to social media. Those dancing in the selfie videos emit an air of confidence, sensuality, and an overall playfulness. What may not be apparent to some viewers however, is that while social media can be an open space where young women and gender queer persons from SWANA communities can express themselves, it can conversely be a dangerous space used to shame and threaten them.

The blackmailing and psychological abuse of women through the threat of publicizing recordings showing their bodies in ways that could be deemed immodest has made global headlines that have also informed Diaz’s work. One such instance was the case of Ghadeer Ahmed, who at the age of 18 sent a video of herself dancing to her boyfriend. After the relationship subsided, the ex posted the video online in an act of revenge and to shame her. Despite Ahmed’s success in having him convicted for defamation, years later, after participating in the Egyptian revolution and pursuing women’s rights activism, the video continued to be used as a means to intimidate and threaten her by other men who sought to discredit her. In an act of defiance and to proclaim her body as a source of pride, she ultimately released the video herself. While the FYEO universe is a space free of humiliation and guarded from the outside world (note even the presence of the transcultural protective symbol of the “evil eye” neon), by featuring videos of evocative dancing and protest movements as well as directly alluding to political activism in the U.S., the potential threats reflected by Ghadeer Ahmed’s experiences loom in the horizon.

The inclusion of women’s voices coming directly from the Global South through the clips of women-led protest movements is another central layer of FYEO. Among the many clips, there is ample footage featuring women from the Arab world participating in protests during the Arab Spring, now at its 10-year anniversary. While it is clear that women from across the region are at the forefront of their ongoing struggles to end discrimination, diasporic communities navigate an additional set of realities. Due to the ongoing vilification of Islam, suspicions towards SWANA cultures, and the hyper-negative portrayals of Muslim men in Western societies, it is often difficult for women and queer persons in the diaspora to speak up publicly against gender-based injustices and toxic behaviors within their communities. The pressure to maintain a unified front with regards to the onslaught of multilateral violence directed at immigrant Muslim or SWANA communities has, at times, had the effect of isolating and censuring critical perspectives from within. Moreover, such women’s voices have regularly been sought out by proponents of pro-Western geopolitical agendas, throughout history and until the present day, as a way to justify supposed Western superiority as well as colonial or neo-imperial occupations of the region. Yet by juxtaposing this diasporic dilemma alongside the ongoing struggles for rights by women across the region and beyond, the FYEO installation generates complex yet hopeful connections rooted in possibilities for the future.

Freedom and rights movements do not exist in a vacuum and are often informed by one another. Diaz’s installation presents a layered constellation of interrelated realities across borders, identities and eras that have the potential to align along intersectional and transnational movements of solidarity. In fact, she herself directly participates in this movement by commissioning other artists to participate in and be part of her work. Diaz reached out to DJ/producer Carol Abi Ghanem, who fittingly also takes part at the forefront of activism in Lebanon, to create music for the FYEO installation. Ava Ansari is yet another invited artist who will use FYEO’s space in a series of live performances entitled The Gray Area where she will release the public’s pain and revisit somatic, sonic, and scenic celebratory memories from her past living in Iran. Such acts of intersectional artistic social practice are at the core of healing traumas and strengthening the bonds between female and non-binary diasporic communities.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Music: Composition by Carol Abi Ghanem, Mixing and mastering by Elie Abi Ischac; Neon fabrication: Mark Chalou

Research assistance: Caitlin Abadir-Mullally

Selfies video contributors:

Alia Scheirman, Amal Amer, Amani Yahya, Angie Assal, Arshia Haq, Aya Metwalli, Bielul Semere, Bita Bell, Caitlin Abadir-Mullally, Danie, Donia Jarrar, Doua Fatfat, Eliane Chahoud, Esraa Warda, Gina Ali, Hamzeh Daoud, Hinna, Iris Zafra, Jesenia Lopez Matos, Kiki Salem, Lama Sami, Layle Omeran, Moumen Eryani, Nadia Khayrallah, Nawal J, Numa Chowdry, Qandeel Baloch, Randa Abboud, Randa Jarrar, Rime, Saif Radi, Salma Dona Taleb, Samira Kha, Sara Stajic, Sarana Mehra, Sheila Govindarajan, Yassa.

YouTube, Vimeo , and social media sources: “Afghan women protest against domestic violence,” YouTube, uploaded by Associated Press, July 30, 2015. “Benat Al Shar3” / بنات الشارع / “Street Girls”, Vimeo, by Lujain Jo, March 7, 2020. “'Blue bra' girl brutally beaten by Egypt military,” YouTube, uploaded by RT, December 18, 2011. “Egyptian leader Gamal Abdel Nasser laughing at hijab requirement in 1958 (subtitled)”, YouTube, uploaded by VideoClips, December 13, 2015. “Feminist Insha’allah: the story of Arab Feminism by Feriel Ben Mahmoud,” film trailer, Vimeo, uploaded by Java Films, February 23, 2015. “40 Million: The Struggle for Women's Rights in Iran," YouTube, uploaded by Time Magazine, March 10, 2020. “Indian women form 620km human chain in support of lifting of temple ban,” The Guardian, January 3, 2019. “Lebanese hold feminist march in Beirut,” YouTube, uploaded by AFP News Agency, November 3, 2019. “Lebanese women kick back,” YouTube, uploaded by BBC Monitoring, November 22, 2019. “Protest in Kolkata. The rapist is you’: Feminists sing Bengali version of Chilean piece to protest Modi’s Kolkata visit,” YouTube, uploaded by Scroll.in, Jan 11, 2020. “Protest over the murder of model Qandeel Baloch,” YouTube, uploaded by Associated Press, November 16, 2016. “Saudi Women Take the Wheel to Protest Religious Ban on Driving,” YouTube, uploaded by PBS Newshour, June 17, 2011. “Yemeni women protest over Saleh criticism” YouTube, uploaded by Al Jazeera, April 16 2011. “Tehran 1980,” YouTube, uploaded by Hamidreza Nabaee, April 9, 2016. “Tunisian women perfom viral feminist anthem "The Rapist is You!" YouTube, uploaded by AFP News Agency, December 14, 2019. “Turkey: Hundreds of women perform "The rapist is you" at Istanbul protest,” YouTube, uploaded by Ruptly, December 15, 2019. “Turkish President says women are not equal,” CNN, November 24, 2014. “Vida Movahed, known as "the girl of Revolution Street" was just sentenced to one year in prison,” YouTube, uploaded by Freedom For Iran, April 14, 2019. @raminmazhar Instagram, October 2, 2022. @IranLionness Twitter, October 30, 2022. @sarahrmni Instagram, October 17, 2022.

Special thanks to: Lila Nazemian, Nay El Rahi, Anuradha Vikram, Hale Ekinci, Sarika Sanyal, Nidal Semlali

2023 OXY ARTS (co-presented with Los Angeles Nomadic Division) Installation build-out: Jeff Ono and Frankie Fleming

TCS dance performance commissioned in response to "For Your Eyes Only" by Yasmine Nasser Diaz. Original choreography by TCS: Téa Devereaux, Chryssa Hadjis, and Simrin Player. Director: Yasmine Nasser Diaz. Videography and editing: Andy Chinn

Made possible with support from the Los Angeles Nomadic Division, the Mellon Foundation, the Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts and the Wilhelm Family Foundation.

2022 Fine Arts Center Gallery, University of Arkansas: Curator and production coordinator: Maryam Amirvaghefi

2021 University of Michigan Institute for the Humanities Curator: Amanda Krugliak; Arts Production Coordinator: Juliet Hinely; Tech consultant: Tom Bray; Installation build-out: Matt Plave, Don Osborne, Jeff Evans, and Chris Basar; Window text and graphic design: Laura Koroncey