photo credit Stacie Jaye Meyer

Exit Strategies

Women’s Center for Creative Work

June 8–August 3, 2018

Installed in 2019 at Habibi House with additional works under the title Dirty Laundry

Alexis Bolter for The Coastal Post

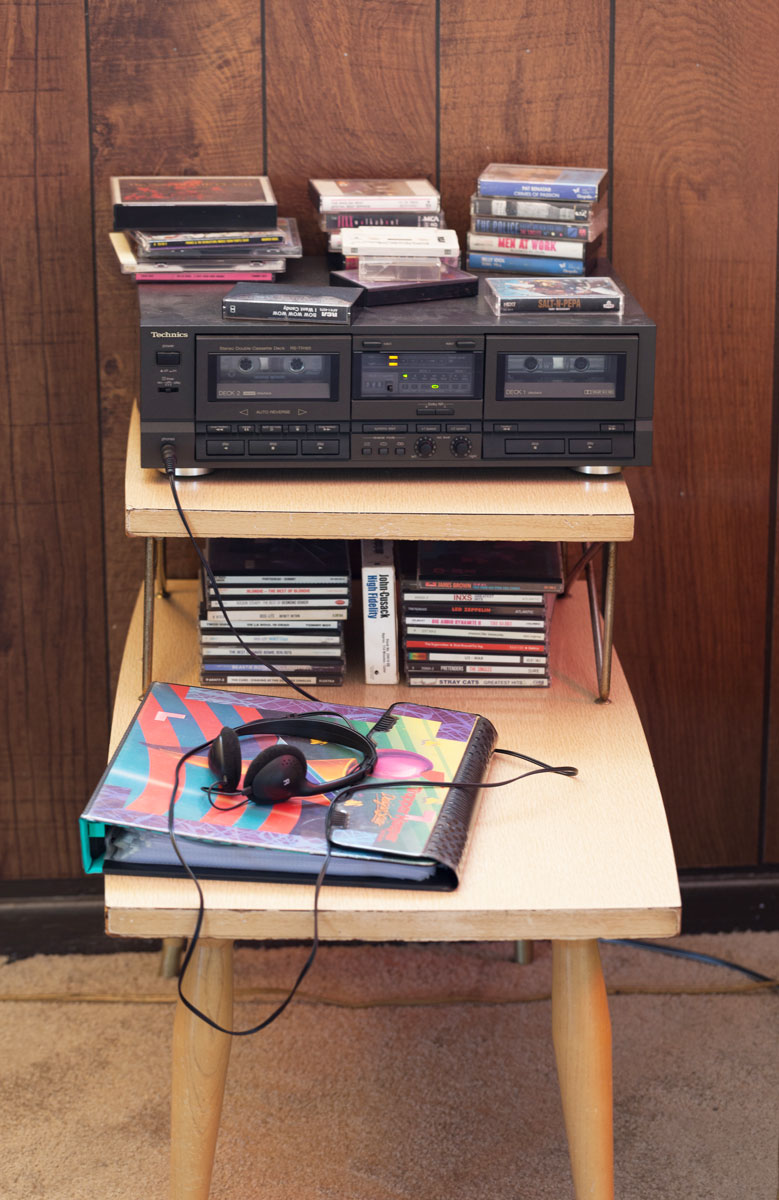

Though we were all far from our teenage years, the opening felt like a house party your friend throws in high school when their parents are away. Yasmine Diaz’s installation, Exit Strategies, encourages this long forgotten youthful behavior. We all crammed into the small room clutching our beers reminiscing under the hot pink glow of the Arabic neon sign. I sat cross-legged on the carpeted floor spilling over a vintage trapper keeper filled with highlighted pages, not of algebra homework, but consisting of the “Multi-agency practice guidelines: Handling cases of Forced Marriage”. During Diaz’s residency at the Women’s Center for Creative Work, she transformed this white-walled space into a replication of the basement bedroom she once shared with her sisters. The installation lures you in with its glowing neon light and Love’s Baby Soft scent and then interrupts your nostalgia by revealing pieces of Diaz’s journey as she escaped the threat of honor violence.

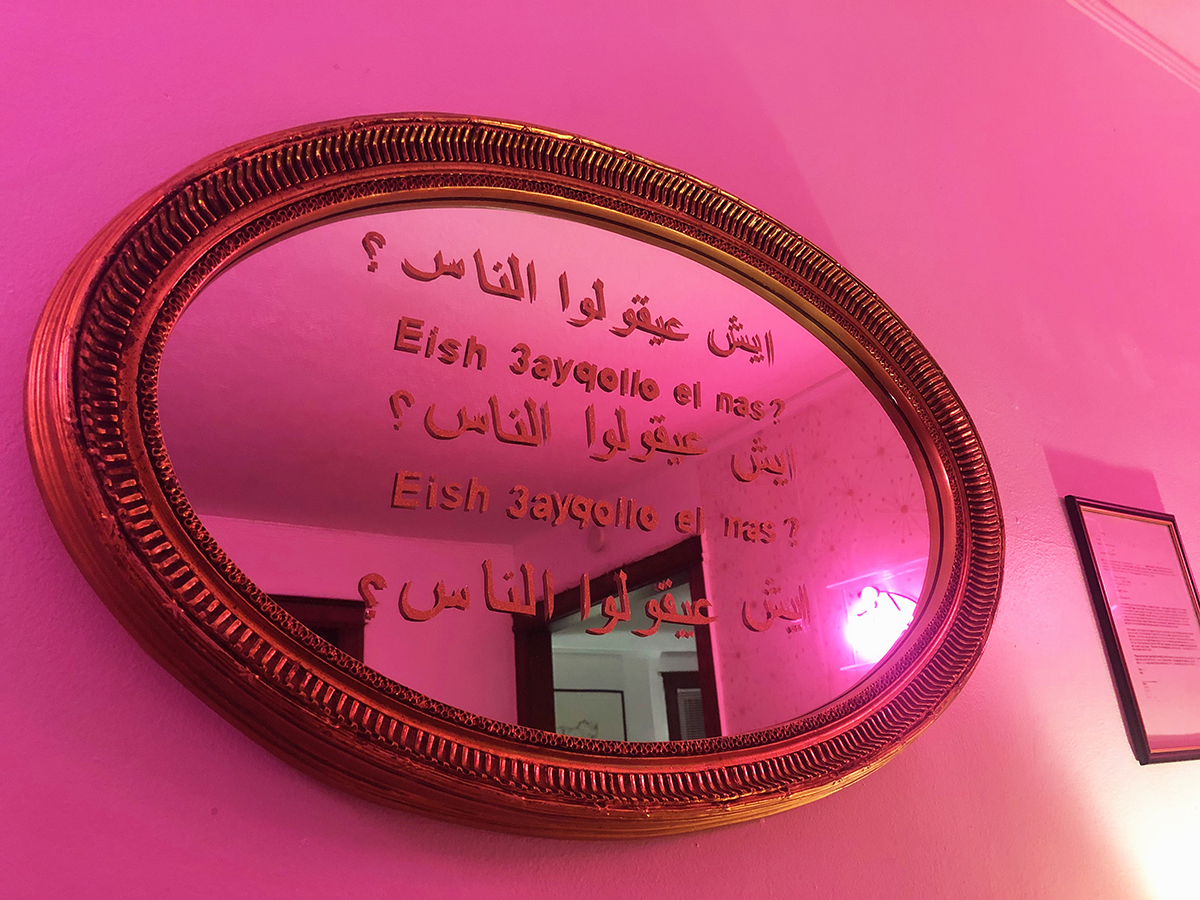

The dominant element of Diaz’s installation is the bright pink neon light. The color quickly becomes a natural element of this retro space but there is much to unpack in this glowing sign. Diaz provides guidance for those of us who cannot read Arabic, “The text in Arabic is matronymic with my mother’s name and the name I had before I changed it to Yasmine.” Rather than following the traditional “daughter of ” naming structure, Diaz has disrupted that patronymic framework to read the “daughter of ”. This act speaks to Diaz’s rebellion against the patriarchy and her willingness to challenge a culture she was born into as a Yemeni-American brought up in a Muslim home.

It should be said that I feel the heavy weight that comes from discussing the topics of Diaz’s installation. Yasmine and I have spent many hours discussing the ideas behind her work and, as I type out these words, I feel the fragility of that conversation magnified. This is the bravery that runs through her practice; she is not shying away from a conversation that involves religion, identity, and gender politics. It may feel uncomfortable to be critical of a religion that is also being unfairly persecuted by our country during this surge of xenophobia yet it also seems wrong to dismiss the gender inequality that can be extracted from that religious ideology. This conversation is made more poignant by its display at the Women’s Center for Creative Work. The cross-section of feminism and conservative Islamic tradition is a space that empowers the hijab but doesn’t necessarily ask questions about how that tradition and other more restrictive practices are carried out. Diaz’s installation and the WCCW are taking the steps to engage in this difficult conversation by creating a space that welcomes that dialog.

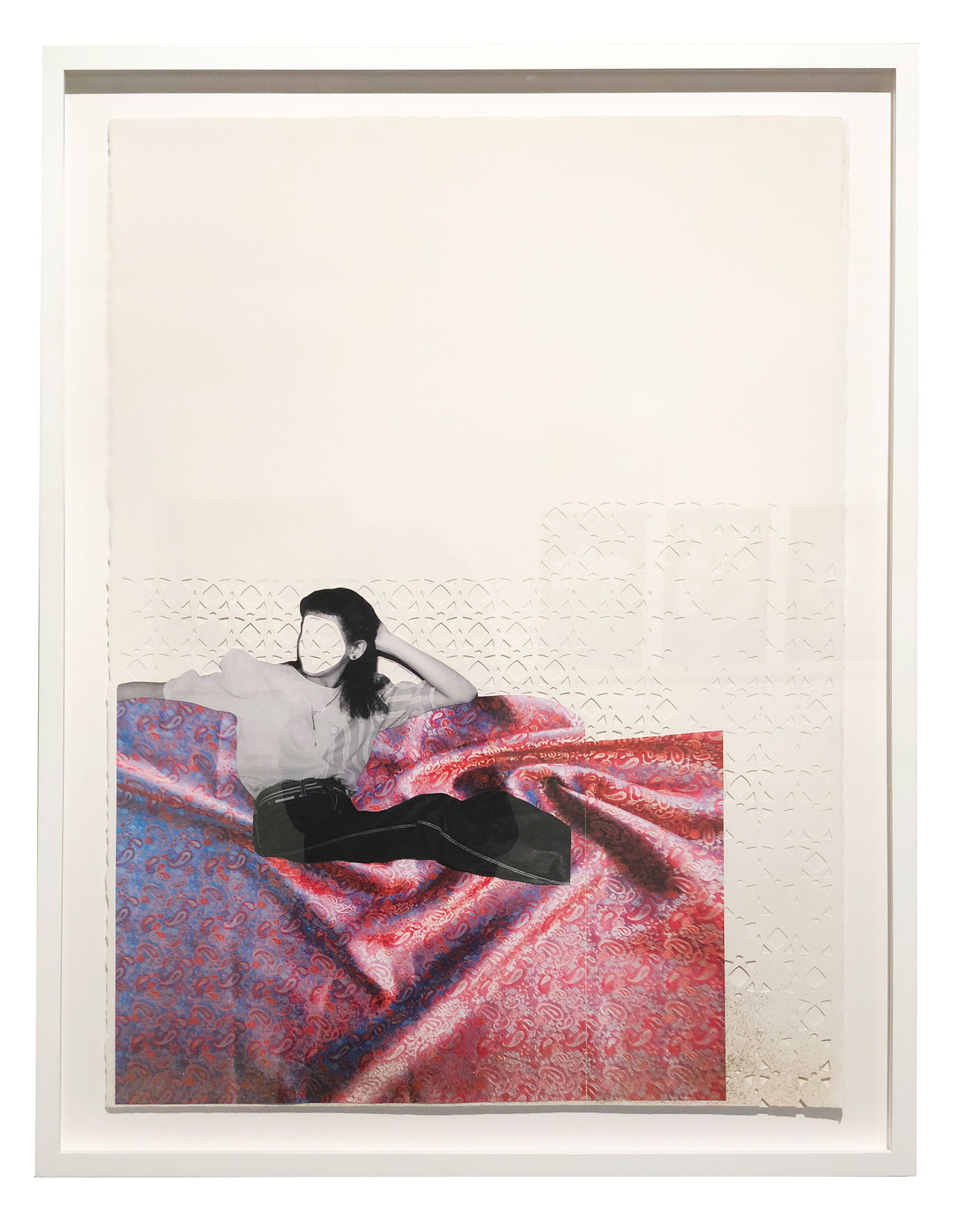

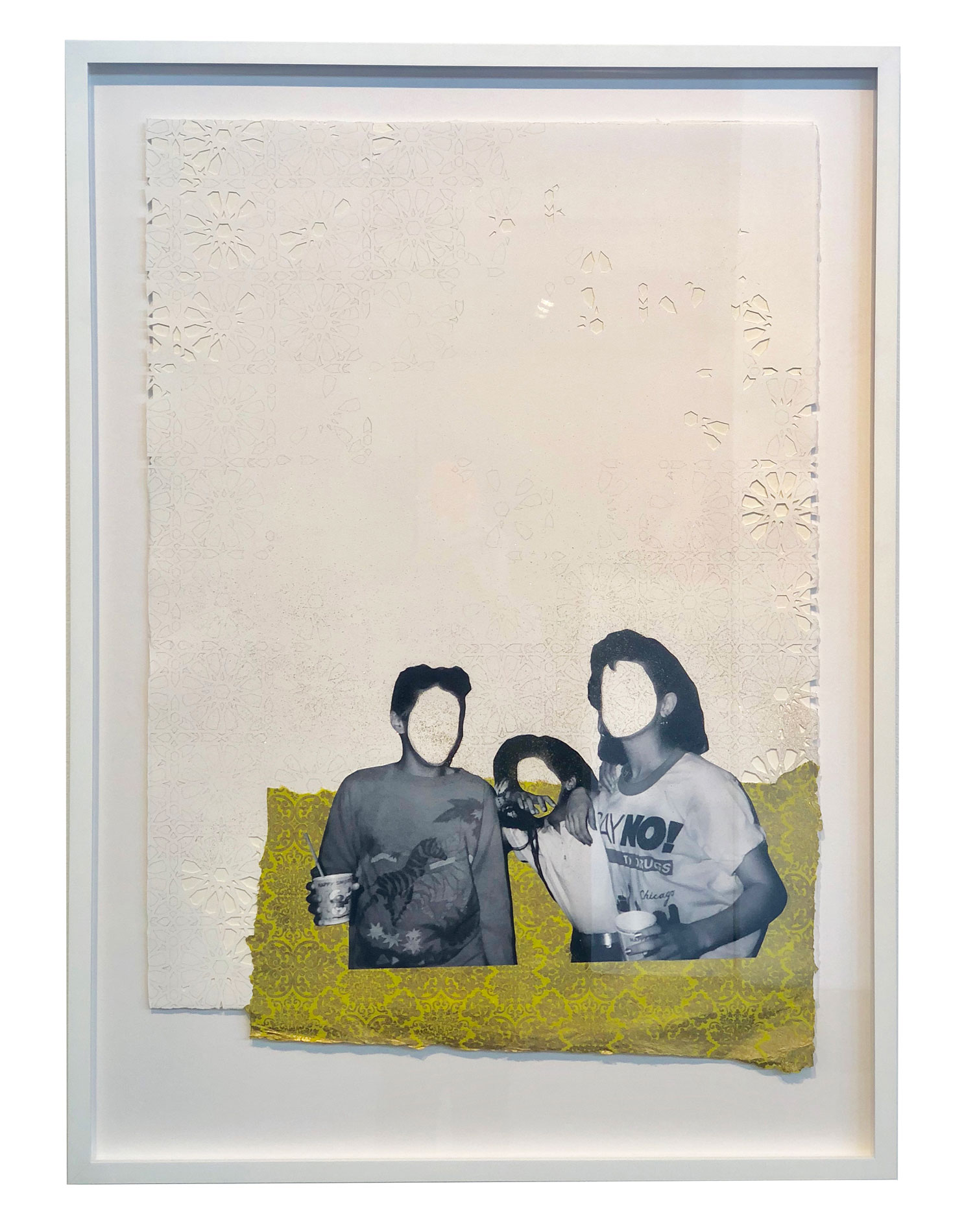

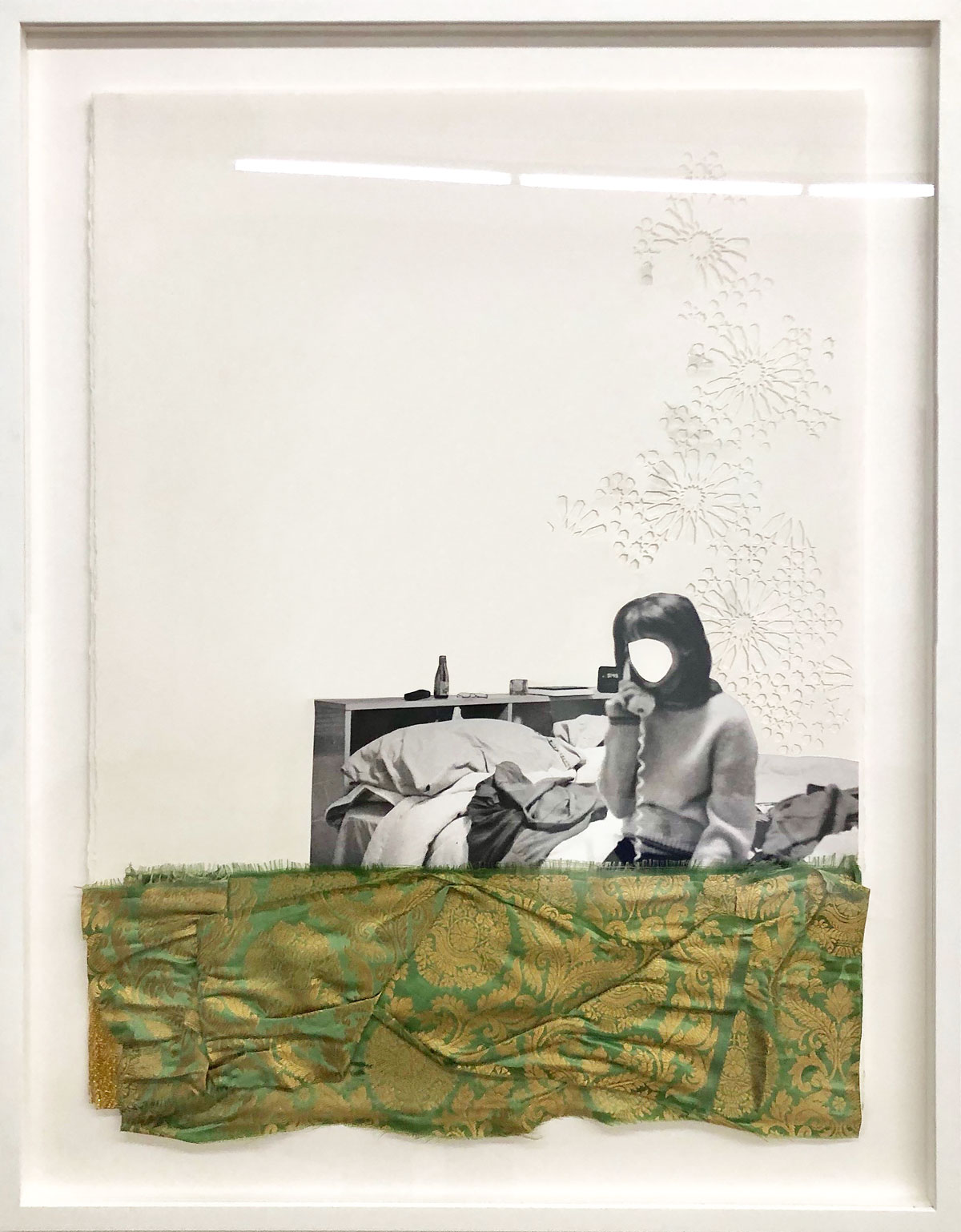

That conversation finds a safe home in the transformed residency space. The familiar wood paneling and mustard hues are cradling a muted carpet and retro furniture. The two wallpaper patterns are striking. One side obviously bought and pasted, the other hand-painted with a pattern that is trying to say something more. Those hand-painted 12-point rosettes reference a style of Islamic geometric tiling which continue off the wall and into the intricate paper cuttings that inhabit the framed collages. The source images used for those collage pieces echo the environment we find ourselves in; a place where young women can let down their guard. But this carefree attitude must be read through the young women’s body language since their faces have been removed. This omission serves as another act of disruption and an act of protection when placed in the context of the framed documents scattered around the installation.

These redacted documents are precious in their creation and harrowing in their journey. What you are able to glean from these email exchanges is that Diaz escaped her childhood home under threat of retaliatory violence as a result of refusing to enter an arranged marriage. This story is illuminated through these correspondences that document Diaz’s attempt to obtain a legal passport after using a false social security number and a false birth certificate while in hiding.

Diaz’s installation is being presented this quarter under the “Control” programming at the Women’s Center. Yasmine has fought against the controlling elements in her life since her time in the basement. In the corner of her installation, you’ll find a pair of shorts clipped to a long skirt, a revealing glimpse into her daily defiance against this imposing control. There is so much courage in this work. The courage to flee her home at a young age, the courage to reveal her false identities, and the courage to revisit that basement with us, the viewer. When I was leaving the opening, I asked Yasmine how she felt about the evening and what it was like to see all these people in her installation. She mentioned how she rarely invited friends over to her room growing up. This installation allowed her to fulfill this childhood desire as she continues to assert her control.